Before World War Two, the Standard Motor Company and Triumph Motor Company were very much separate entities, despite the fact that Siegfried Bettmann, founder of the Triumph Motor Cycle company had owned a stake in Standard since 1912. The impact of World War Two had a profound effect on both companies and was a major element to the acquisition by Standard, of the failed Triumph company after the war.

Standard had struggled through the 1920s with falling profits, failing export contracts and sluggish sales on larger models. Founder, Reginald Maudslay retired in 1934 and died soon afterwards with Charles Band, a Coventry solicitor and a Standard director since 1920, then becoming Chairman.

However, the 1930s saw something of a transformation for the company. This was due, in part, to the arrival of a new leader in 1929, as one Captain John Black was appointed as joint Managing Director.

Standard were reliant on their new models to bring them fortune through the thirties and they were doing well. The Standard 9 and Standard Ten were selling on target and they were supplying engines and chassis to William Lyons for the SS Car Company, who were busy building cars based on Standard components that would lay the groundwork for what would become Jaguar, after the war.

1936 saw the arrival of the Flying Standards that had been unveiled the year before at the motor show, with their ‘streamlined’ bodies and ‘waterfall’ grilles.

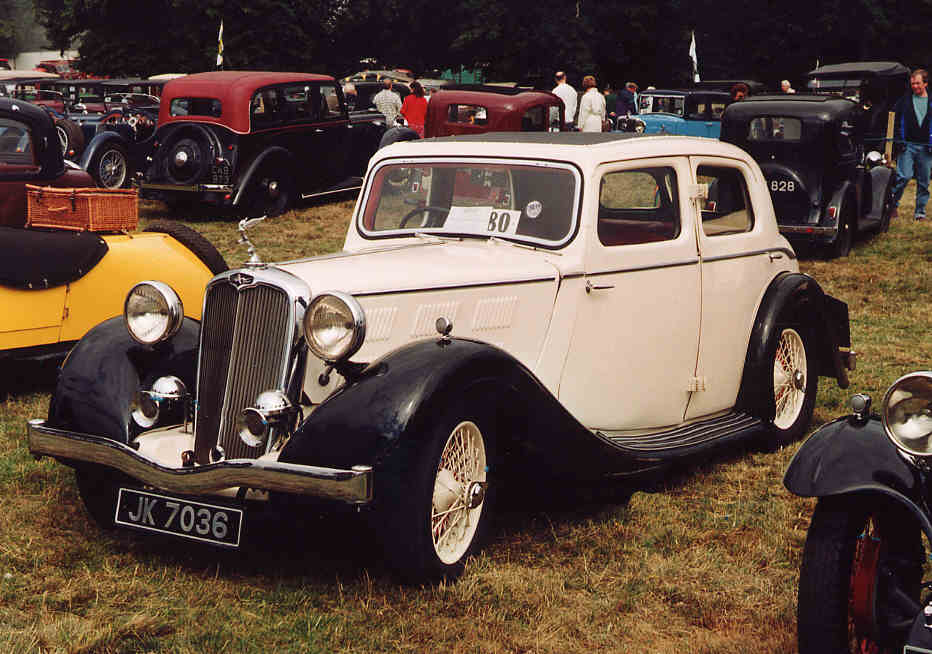

Flying Twelve from 1938

By the end of the 1930s, Standard were churning out over 50,000 cars a year from their Canley plant, quite impressive scales for the period.

1938 heralded the opening of Standard’s new factory at Fletchampstead and the launch of the Flying Eight, which was to enjoy the accolade of being the first British saloon car with independent front suspension. The technology would be rolled out to the Flying Ten and Twelve the same year.

Meanwhile, over at Triumph, they had been paying Lea Francis a commission on every Triumph 10/20 sold as part of the deal for the company designing the car for them. Few were sold, but volumes ramped up with the Triumph Super 7 which sold well until 1934. The then General Manager, Claude Holbrook decided that competing with the mass market suppliers like Austin was going to be impossible. Having seen what some other small-scale luxury or sporting brands like SS and MG were achieving, he decided the way to go was to build high-end, expensive, exclusive sporting cars. He introduced the exotic and upwardly mobile sounding Triumph Gloria Southern Cross. They used engines designed for them by Coventry Climax, who drew up the plans but left Triumph to do the actual construction in-house.

Triumph Gloria

But by 1937, they had a bright spark designer on the up in their midst, who enabled the company to build engines to their own specifications. His name, was Donald Healey and he had been appointed as experimental manager in 1934. By 1937, his engines were in full swing.

To get into the mindset of Holbrook and Healey at the time and how they saw the Triumph brand growing through the 1930s, the first Dolomite is a good barometer. It was designed by Donald Healey after he bought (no doubt on the company credit card) an Alfa Romeo 8C. A car that was as incredibly expensive and exotic then, as it is now. By using the straight-8 engines from the Alfa as inspiration, Triumph built three cars in 1934 carrying the Dolomite name, one of which was smashed up by Healey on the Monte Carlo in 1935 when he had an argument with a train on a railway crossing in Denmark and quite clearly lost. To give you an idea of just how expensive these cars were, an average Austin at the time was around £100. The 8-cylinder Dolomites were priced at £1,050!

The Dolomite name was later used on a different range of cars, saloons this time, built in the last few years before the war 1937 to 1940. The design featured a new radiator grille styled by a young Walter Belgrove who would later go on to design the concept car for our beloved TRs, the TRX. The Dolomites were sold as "the finest in all the land" and were aimed squarely at luxury sporting saloon market, a sort of BMW M3 equivalent in today’s money, for the last years before the war.

Dolomites at Gaydon, By FDS2 - CC BY-SA 3.0,

By the time the famous “This country is at war with Germany” speech by Neville Chamberlain had rung out on wireless sets across the land in 1939, disaster had struck the Triumph Motor Company. In July of 1939, they had gone into receivership. A scrap metal, shipbreaking and cement merchant bought Triumph, (yes really) by the name of Thomas William Ward. They were a Sheffield based company that had established the Portland Cement brand. One of their works is still in operation today at Ketton in Rutland.

They kept Healey on and put him in charge of the company, but the war by now was far from ‘phoney’ and in 1940 the Holbrook Lane works were completely destroyed by bombing.

It is fair to say that Coventry was seriously 'duffed up' by the Luftwaffe. On the 14th November 1940, the city suffered a monumental aerial attack, codenamed 'Moonlight Sonata' by German forces. Nearly 600 people died, 863 were badly injured and 4,300 houses were quite literally flattened. Even Coventry’s medieval cathedral was set on fire.

Car production and all activity completely ceased and for Healey, bigger things for him personally would eventually beckon of course.

But all was not lost for Triumph, it would re-surface towards the end of the war when Standard purchased the trading name in November 1944 and created The Triumph Motor Company (1945) Limited. Standard paid just £75,000 for the company.

The British Motor Industry in 1939 was larger and more economically essential for the UK as a whole than it is today. But in 1939, everything changed. Car manufacturer’s factories would be requisitioned during the war and many others in the supply chain would also turn their attentions to war production including SU carburettors, Dunlop tyres and Smiths gauges - to name but a few.

Very few personal cars, commercial vehicles or even parts for private cars were made during the war and fuel was heavily rationed. Non – essential car journeys were discouraged (does that sound familiar?) and many private motor cars went into storage for the duration of the war. The fact that we have examples of pre-war vehicles to enjoy to this day is itself, nothing short of a miracle, as almost anything metal that wasn’t in regular use was either re-purposed or recycled into products for the war effort.

What is certain with historical hindsight is that, without the active British motor industry, the war could well have had a very different outcome.

Standard, our saviours of the Triumph brand, were a critical player in the war effort. Firstly, they were one of the few manufacturers allowed to continue building passenger cars as many of them went into transportation for the armed forces – albeit dressed up in utility bodies known as “Tillys” to their friends.

Standard’s contribution to the war effort really came to the fore through the incredible aircraft they were responsible for building, namely the legendary de Havilland Mosquito. It was the fastest and arguably most beautiful fighter plane in the RAF and was to be later made famous by their depiction in the epic, but fictional, 633 Squadron film.

De Havilland Mosquitoe

Standard made 1,100 FB VI Mosquitoes, plus 750 Airspeed Oxfords, a whopping 20,000 Bristol Mercury VIII aircraft engines and 3,000 fuselages for Beaufighters. Just take a moment to let the sheer volume of planes that represents sink in. A sobering thought when you imagine how many were destroyed in conflict.

It didn’t end there either, because Standard also created a small armoured Jeep called the Beaverette, of which they produced around 4,000 examples.

The aero engine plant was at Banner Lane, Coventry and was referred to as a ‘shadow factory’. During the war, a number of aptly named ‘shadow factories’ were built, not by car companies but by Government.

Many of these 'shadow factories' had already been built before the war in anticipation of it all 'kicking off' and after battle was declared, were run by the motor industry specifically for the Air Ministry. The workforce was made up of predominantly women as men were conscripted and sent to the front line.

Banner Lane was vast. It was one of the biggest of all the 'shadow factories' and was quite unique, as it had been designed by the UK Government's own architects. The 80-acre site had approximately 1 million square feet of operating floor built out of a green field site on what was then, the outskirts of Coventry. It was built at the Government's expense, like all 'shadow factories' and cost an estimated £1.7million. During operations, the Standard Motor Company were paid £40k a year to manage it.

After VE Day was declared and demand for aero engines ended, Standard used Banner Lane to do a deal to build Ferguson Tractors there instead. Standard took a ten - year lease from the Air Ministry for Banner Lane and Harry Ferguson's agricultural masterpieces were produced in vast numbers, with over half a million being made by nearly 6,000 employees.

Ferguson Tractors were made in vast numbers at Banner Lane

Disagreements happened between Ferguson and (now a Sir) John Black which resulted Standard killing the deal, and cutting all ties. The assets, including Banner Lane, were sold on to Massey Ferguson in 1959 who would use the plant until 2002 when it was developed for housing.

More disagreements happened between Sir John Black and his old pal, Sir William Lyons. Before the war, the two had gotten along just fine, with Standard supplying chassis and engines to SS Cars. But when Sir William Lyons emerged from the war years with a sporting brand in Jaguar that was on the up, Sir John Black was having none of it and focused his attentions squarely in reviving the Triumph name as a sporting brand once again to teach Lyons and his Jaguar idea a jolly good lesson. A similar disagreement following a failed purchase of Morgan would eventually lead to the Triumph TR sports cars emerging in 1953.

It would prove to be his final act, as Sir John Black was eventually forced to retire in 1954 after the TR was launched, and was replaced by Alick Dick.

An early decision in the 1950s would see the Triumph name used as the sporting brand of Standard who, before the launch of the compact 8 saloon in 1953, only had the Vanguard in their line-up. The Triumph Roadster, Mayflower and Renown all paved the way for Triumph becoming the dominant brand by the end of the 1950s. Eventually the Standard Vanguard was replaced with the Triumph 2000 and the Triumph Herald would take the place of the Standard 8 and 10. Triumph also finally achieved sporting success with the TR range however, which lasted gloriously until 1982.

Words by Wayne Scott for TR Register

There are 5 comments on this thread

Use the box below to leave your comments and feedback on the articles above. Please be aware that in some cases comments will be sent to a moderator for approval before going live. The admin team reserve the right to remove comments with inappropriate or offensive content.

If you have an enquiry or a question about any of the articles, either click the author name to contact directly or get in touch with the TR Register.

Hi Wayne . Brilliant work and very readable. 633 Squadron was fictitious. l had no idea of the contribution made by the works. And it seems Sir John Black was his own man , we'll leave it there! Thanks Wayne.

A wonderful and informative article, I had no idea how important Standard were to the war effort.

What a very concise and informative history, written with wit and style.

I was a Leyland Motors (Lancs) graduate apprentice, and moved to Triumph at Canley in 1965. I did a spell as a production foreman in the T2000 Trim Shop, and then as PA to firstly Cliff Swindle, the General Manager, and then Bill Davis when he took over as Chairman. Very different men, but both wonderful!

I feel that Triumph had the potential and creative talents to become the UK's BMW, and to have thrived to this day, but they got lost in the rest of the horrible history of our motor industry.

I have a TR4, which I have owned for 39 years, as the 3rd owner. It links me back to happy times at Canley.

Don Toone

Standard Flying 8

I purchased one back in 1988 as a non runner for the grand some of £250, only the second owner. Suicide doors, 6volt system, I eventually used it for 18 months then sold it for £1100 to buy the trim for my Tr5

Fascinating stuff, thank you Wayne. My very first car was a 1948 Standard 8 saloon, bought for £2.50 shillings (yes really!) when I was an impecunious student. The fact that the brakes didn't work may have influenced the price! My flatmates and I had many adventures with this car, to many to mention here, but after 6 months I had a couple of students who wanted to buy it and after a bit of an 'auction' I sold it for £46! (and then bought an MG TC) Happy days!

Comment notes

Please keep the discussion friendly. Reply's are limited to 2 - if you have more to say why not contact the office, start a thread on the TR Register Forum or start your own Owners Diary.